I am sure that some are born to write as trees are born to bear leaves: for these, writing is a necessary mode of their own development. If the impulse to write survives the hope of success, then one is among these. If not, then the impulse was at best only pardonable vanity, and it will certainly disappear when the hope is withdrawn.

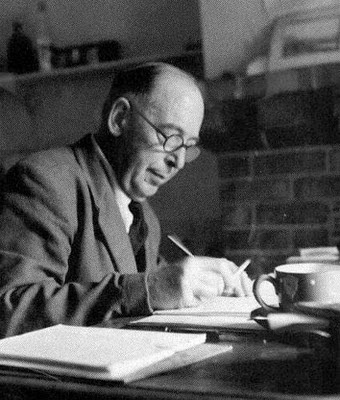

C.S. Lewis to Arthur Greeves,

The Letters of C.S. Lewis, (28 August 1930)

The way for a person to develop a style is (a) to know exactly what he wants to say, and (b) to be sure he is saying exactly that. The reader, we must remember, does not start by knowing what we mean. If our words are ambiguous, our meaning will escape him. I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate open to the left or right the readers will most certainly go into it.

C.S. Lewis, God in the Dock,

"Cross-Examination" (1963)

Returning to work on an interrupted story is not like returning to work on a scholarly article. Fact, however long the scholar has left them untouched in his notebook, will still prove the same conclusions; he has only to start the engine running again. But the story is an organism: it goes on surreptitiously growing or decaying while your back is turned. If it decays, the resumption of work is like trying to coax back to life an almost extinguished fire, or to recapture the confidence of a shy animal which you had only partially tamed at your last visit.

C.S. Lewis, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century,

bk III.I (1954)