Do grown-ups have any business reading The Hobbit? A book about dwarves (Tolkien insisted on this plural), elves, and a race of small people with furry feet, called hobbits, not to mention a wizard, a dragon, and a magic ring - surely these are cliches of fantastic fiction, which adults need not take seriously. What's more, unlike Tolkien's masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, which was clearly intended for adults, he wrote the original version of The Hobbit for reading aloud to his own children. (No he didn't - ed.)

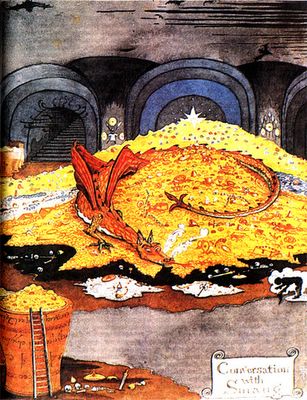

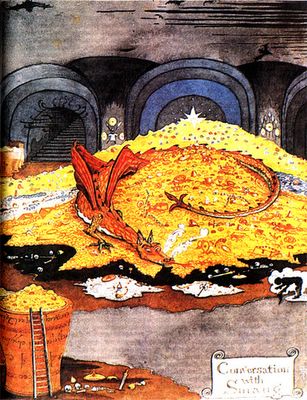

I would beg to differ. The story of a comfort-loving hobbit who finds himself recruited as a burglar by 13 dwarves keen to avenge the deaths of their forefathers and to recover their ancestral treasure from a dragon has a great deal to tell us about courage - a virtue as important today as it was in the Anglo-Saxon times that Tolkien studied professionally.

Bilbo Baggins is far from being an ancient heroic warrior like Beowulf, though it would have been easy for Tolkien to create a cowardly character who soon leaves behind any sensation of fear and is transformed into a great hero of the old mode. Not not only does Bilbo not kill the dragon: he spends much of the climactic Battle of Five Armies knocked unconscious. On the other hand, only Bilbo has the courage to confront the dragon in his lair, and the humanity to try to stop the fighting.

Tolkien's most perceptive critic to date, Tom Shippey, argues that the hobbits are a bridge between our modern world of safe domesticity and pocket-handkerchiefs (Bilbo discovers he hasn't got any when he runs out of his house to join the dwarves in their adventure), and the frightening but exciting world of heroism, myth, and legend.

Professor Shippey writes: "Much of The Hobbit is about the clash of styles, attitudes, and behaviour patterns [between these two worlds] - though in the end one might conclude that they are not as far apart as they first seemed; that Bilbo has just as much right to the archaic world and its treasures as Thorin or Bard [the heroic warriors]"

(J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the century, HarperCollins, 2001).

But there is more to The Hobbit than an exploration of courage. In Tolkien's essay "On fairy stories", written soon after the publication of The Hobbit, he argued that such stories offer, in addition to the benefits of all good literature, special values that he called "Fantasy, Recovery, Escape, Consolation, all things of which children have, as a rule, less need than older people", adding wryly: "Most of them are nowadays very commonly considered to be bad for anybody"

(Tree and Leaf, George Allen & Unwin, 1964).

'Fantasy' is not a word with high status in contemporary Western culture. Indeed, so impoverished is our view of the imagination that popular entertainment prefers the contrivances of reality TV to made-up stories, and some serious writers can add gravitas to their work only by transcribing the actual words of people caught up in historic events. But, for Tolkien, the imagination was one of our most distinctively human attributes: a key element of the divine image in human beings.

He called the creation of an imaginatively consistent secondary world 'sub-creation', and wrote in a poem that he gave to C. S. Lewis (and which was a significant factor in Lewis's conversion to Christianity) "we make still by the law in which we are made" (quoted in

Tree and Leaf).

By 'Recovery', Tolkien meant a rediscovery of the freshness and vitality of the world, especially the natural world and humanity's pre-industrial artefacts, such as bread and wine. Fairy stories help to free us from the drabness and triteness of our contemporary view of the world, where the enormous material wealth many of us have has blurred our vision and narrowed our focus to 'getting and spending', as William Wordsworth put it.

In praising 'Escape', Tolkien knew he was moving on to controversial ground, but, as he said, the people who are most against anyone's escaping are jailers. "Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?"

'Consolation' was only one of Tolkien's names for what he regarded as the highest value of the fairy tale. By it, he meant that all true and complete fairy stories must have a happy ending, which he also called 'eucatastrophe', "a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur". He saw this as "a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief".

Unperceptive critics of Tolkien often accuse him of writing sentimental happy endings. In fact, Tolkien viewed life with a robust honesty, not denying that the world is full of suffering (both his parents had died by the time he was 12, and he fought in the First World War), and yet insisting that salvation can come when it is least expected.

Perhaps the most striking example of this in The Hobbit is when, at the climax of the Battle of Five Armies, Bilbo cries out: "The Eagles are coming!" There may be an implicit reference here to Christian iconography, but, more importantly, it underlines the fact that, no matter how hard we strive, we have no power, of ourselves, to save ourselves.

Jennifer Swift

(A fiction writer, a member of the Oxford C. S. Lewis Society, and has taught courses on the Inklings).

The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien is published by HarperCollins.

Published in the Church Times - 3rd November 2006