This is one of the most freshly original and delightfully imaginative books for children that have appeared in many a long day. Like "Alice in Wonderland," it comes from Oxford University, where the author is Professor of Anglo-Saxon, and like Lewis Carroll's story, it was written for children that the author knew (in this case his own four children) and then inevitably found a larger audience.

The period of the

story is between the age of Faerie and the dominion of men. To an adult who

reads of Smaug the Dragon and his hoard, won by the dwarves but claimed also by

the Lake men and the Elven King, there may come the thought of how legend and

tradition and the beginning of history meet and mingle, but for the reader from

8 to 12 "The Hobbit" is a glorious account of a

magnificent adventure, filled with suspense and seasoned with a quiet humor

that is irresistible.

Hobbits are (or

were) a small people, smaller than dwarves - and they have no beards - but very

much larger than liliputians. There is little or no magic about them, except

the ordinary everyday sort which helps them to disappear quietly and quickly

when large, stupid folk like you and me come blundering along, making a noise

like elephants which they can hear a mile off. They are inclined to be fat in

the stomach; they dress in bright colors, chiefly green and yellow; wear no

shoes because their feet grow natural leathery soles and thick, warm brown

hair; have long, clever, brown fingers, good-natured faces and laugh deep,

fruity laughs (especially after dinner, which they have twice a day, when they

can get it).

Bilbo Baggins was a

hobbit whom we find living in his comfortable, not to say luxurious, hobbit

hole, for it was not a dirty, wet hole, nor yet a bare, sandy one, but inside

its round, green door, like a porthole, there were bedrooms, bathrooms,

cellars, pantries, kitchens and dining rooms, all in the best of hobbit taste.

All Bilbo asked was to be left in peace in this residence, known as

"Bag-End," for hobbits are naturally homekeeping folk, and Bilbo had

no desire for adventure. That is to say, the Baggins' side of him had not, but

Bilbo's mother had been a Took, and in the past the Tooks had intermarried with

a fairy family. It was the Took strain that made the little hobbit, almost against

his will, respond to the summons of Gandalf the Wizard to join the dwarves in

their attempt to recover the treasure which Smaug the dragon had stolen from

their forefathers. Bilbo has an engaging, as well as an entirely convincing,

personality; frankly scornful of the heroic (except in his most Tookish

moments), he nevertheless plays his part in emergencies with a dogged courage

and resourcefulness that make him in the end the real leader of the expedition.

After the dwarves

and Bilbo have passed "The Last Homely House" their way led through

Wilderland, over the Misty

Mountains

The tale is packed

with valuable hints for the dragon killer and adventurer in Faerie. Plenty of

scaly monsters have been slain in legend and folktale, but never for modern

readers has so complete a guide to dragon ways been provided. Here, too, are

set down clearly the distinguishing characteristics of dwarves, goblins, trolls

and elves. The account of the journey is so explicit that we can readily follow

the progress of the expedition. In this we are aided by the admirable maps

provided by the author, which in their detail and imaginative consistency,

suggest Bernard Sleigh's "Mappe of Fairyland."

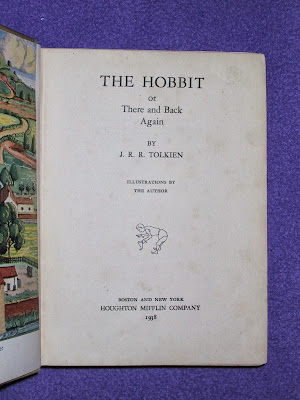

The songs of the

dwarves and elves are real poetry, and since the author is fortunate enough to

be able to make his own drawings, the illustrations are a perfect accompaniment

to the text. Boys and girls from 8 years on have already given "The

Hobbit" an enthusiastic welcome, but this is a book with no age limits.

All those, young or old, who love a fine adventurous tale, beautifully told,

will take "The Hobbit" to their hearts.

Anne T.

Eaton

New York Times -- March 13, 1938

New York Times -- March 13, 1938