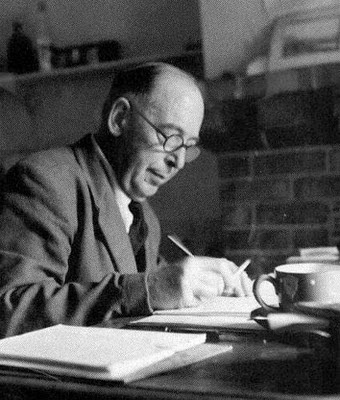

Dear Meredith,

1. Why did I become a writer? Chiefly, I think, because my clumsiness or fingers prevented me from making things in any other way. See my Surprised by Joy, chapter I.

2. What inspires my books? Really I don't know. Does anyone know where exactly an idea comes from? With me all fiction begins with pictures in my head. But where the pictures come from I couldn't say.

3. Which of my books do I think most "representational"? Do you mean (a.) Most representative, most typical, most characteristic? or (b.) Most full of "representations" i.e. images. But whichever you mean, surely this is a question not for me but for my readers to decide. Or do you mean simply which do I like best? Now the answer would be Till We Have Faces and Perelandra.

4. I have, as usual, dozens of "plans" for books, but I don't know which, if any, of these will come off. Very often a book of mine gets written when I'm tidying a drawer and come across notes for a plan rejected by me years ago and now suddenly realize I can do it after all. This, you see, makes predictions rather difficult!

5. I enjoy writing fiction more than writing anything else. Wouldn't anyone?

Good luck with your "project."

yours sincerely,

C.S. Lewis

Letters to Children (1985), letter of 6 December, 1960

Monday 25 December (1922)

We were awakened early by my father to go to the Communion Service. It was a dark morning with a gale blowing and some very cold rain. We tumbled out and got under weigh. As we walked down to church we started discussing the time of sunrise; my father saying rather absurdly that it must have risen already, or else it wouldn't be light.

In church it was intensely cold. W offered to keep his coat on. My father expostulated and said "Well at least you won't keep it on when you go up to the Table." W asked why not and was told it was "most disrespectful". I couldn't help wondering why. But W took it off to save trouble. I then remembered that D was probably turning out this morning for Maureen's first communion, and this somehow emphasised the dreariness of this most UNcomfortable sacrament. We saw Gundrede, Kelsie and Lily. W also says he saw our cousin Joey...

We got back and had breakfast. Another day set in exactly similar to yesterday. My father amused us by saying in a tone, almost of alarm, "Hello, it's stopped raining. We ought to go out," and then adding with undisguised relief "Ah, no. It's still raining: we needn't." Christmas dinner, a rather deplorable ceremony, at quarter to four. Afterwards it had definitely cleared up: my father said he was too tired to go out, not having slept the night before, but encouraged W and me to do so - which we did with great eagerness and set out to reach Holywood by the high road and there have a drink. It was delightful to be in the open air after so many hours confinement in one room.

Fate however denied our drink: for we were met just outside Holywood by the Hamilton's car and of course had to travel back with them. Uncle Gussie drove back along the narrow winding road in' a reckless and bullying way that alarmed W and me, We soon arrived back at Leeborough and listened to Uncle Gussie smoking my father in his usual crude but effective way, telling him that he should get legal advice on some point. The Hamiltons did not stay very long.

Afterwards I read Empedocles an Etna wh. I read long ago and did not understand. I now recognised Empedocles' first lyric speech to Pausanias as a very full expression of what I almost begin to call my own philosophy. In the evening W played the gramophone. Early to bed, dead tired with talk and lack of ventilation. I found my mind was cumbling into the state which this place always produces: I have gone back six years to be flabby, sensual and unambitious. Headache again.

C.S. Lewis

All My Road Before Me

from "The Greater Trumps"

She took a step forward, and her heart beat fast and high as she seemed to move into the clouded golden mist that received her, and fantastically enlarged and changed the appearance of her hands and the cards within them. She took another step, and the Tarots quivered in her hold, and through the mist she saw but dimly the stately movement of the everlasting measure trodden out before her, but the images were themselves enlarged and heightened, and she was not very sure of what nature they were. But nothing could daunt the daring in which she went; she took a third step, and Henry's voice cried to her suddenly, "Stop there and wait for the cards."

She half-turned her head towards him at the words, but he was too far behind for her to see him. Only, still looking through that floating and distorting veil of light, she did see a figure, and knew it for Aaron's: yet it was more like one of the Tarots - it was the Knight of Sceptres. The old man's walking-stick was the raised sceptre; the old face was young again, and yet the same. The skull-cap was a heavy medieval head-dress - but as the figure loomed it moved also, and the mist swirled and hid it. The cards shook in her hands; she looked back at them, and suddenly one of them floated right out into the air and slowly sank towards the floor; another issued, and then another, and so they followed in a gentle persistent rain. She did not try to retain them; could she have tried she knew she could not succeed. The figures before her appeared and disappeared, and as each one showed, so in spiral convolution some card of those she still held slipped out and wheeled round and round and fell from her sight into the ever-swirling mist.

Chapter 5 "The Image that did not move"

Charles Williams

My heart and mind is in the Silmarillion...

[Image : 76 Sandfield Road, Oxford]

My heart and mind is in the Silmarillion, but I have not had much time for it. ....

It may amuse you to hear that (unsolicited) I suddenly found myself the winner of the International Fantasy Award, presented (as it says) 'as a fitting climax to the Fifteenth World Science Fiction Convention'. What it boiled down to was a lunch at the Criterion yesterday with speeches, and the handing over of an absurd 'trophy'. A massive metal 'model' of an upended Space-rocket (combined with a Ronson lighter). But the speeches were far more intelligent, especially that of the introducer: Clémence Dane, a massive woman of almost Sitwellian presence. Sir Stanley himself was present. Not having any immediate use for the trophy (save publicity=sales=cash) I deposited it in the window of 40 Museum Street. A back-wash from the Convention was a visit from an American film-agent (one of the adjudicating panel) who drove out all the way in a taxi from London to see me last week, filling 76 S[andfield] with strange men and stranger women -1 thought the taxi would never stop disgorging. But this Mr Ackerman brought some really astonishingly good pictures (Rackham rather than Disney) and some remarkable colour photographs. They have apparently toured America shooting mountain and desert scenes that seem to fit the story. The Story Line or Scenario was, however, on a lower level. In fact bad. But it looks as if business might be done. Stanley U. &: I have agreed on our policy : Art or Cash. Either very profitable terms indeed; or absolute author's veto on objectionable features or alterations.

J.R.R. Tolkien

From a letter to Christopher and Faith Tolkien

11 September 1957

Look for Truth first

Christianity tells people to repent and promises them forgiveness. It therefore has nothing (as far as I know) to say to people who do not know they have done anything to repent of and who do not feel that they need any forgiveness.

It is after you have realized that there is a real Moral Law, and a Power behind the law, and that you have broken that law and put yourself wrong with that Power - it is after all this, and not a moment sooner, that Christianity begins to talk. When you know you are sick, you will listen to the doctor. When you have realized that our position is nearly desperate you will begin to understand what the Christians are talking about. They offer an explanation of how we got into our present state of both hating goodness and loving it. They offer an explanation of how God can be this impersonal mind at the back of the Moral Law and yet also a Person. They tell you how the demands of this law, which you and I cannot meet, have been met on our behalf, how God Himself becomes a man to save man from the disapproval of God...

I quite agree that the Christian religion is, in the long run, a thing of unspeakable comfort. But it does not begin in comfort; it beings in the dismay I have been describing, and it is no use at all trying to go on to that comfort without first going through that dismay. In religion, as in war and everything else, comfort is the one thing you cannot get by looking for it. If you look for truth, you may find comfort in the end: if you look for comfort you will not get either comfort or truth - only soft soap and wishful thinking to begin with and, in the end, despair.

C.S. Lewis

Mere Christianity (1943)

Before Morgoth's Throne

Beren and Lúthien before Morgoth's Throne in Angband. The battle in song before the throne, from the most important (IMHO of course) of all of Tolkien's works, and the composition that he returned to the most. Why do I say this? On his grave in Wolvercote Cemetery, as well as the details of J.R.R.T. and his wife Edith, are two words, "Beren and Lúthien".

In his eyes the fire to flame was fanned,

and forth he stretched his brazen hand.

Lúthien as shadow shrank aside.

'Not thus, O king! Not thus!' she cried,

'do great lords hark to humble boon!

For ever minstrel hath his tune;

and some are strong and some are soft,

and each would bear his song aloft,

and each a little while be heard,

though rude the note, and light the word.

But Lúthien hath cunning arts

for solace sweet of kingly hearts.

Now hearken!' And her wings she caught

then deftly up, and swift as thought

slipped from his grasp, and wheeling round,

fluttering, before his eyes, she wound

a mazy-wingéd dance, and sped

about his iron-crownéd head.

Suddenly her song began anew;

and soft came dropping like a dew

down from on high in that domed hall

her voice bewildering, magical,

and grew to silver-murmuring streams

pale falling in dark pools in dreams.

She let her flying raiment sweep,

enmeshed with woven spells of sleep,

as round the dark void she ranged and reeled.

From wall to wall she turned and wheeled

in dance such as never Elf nor fay

before devised, nor since that day;

than swallow swifter, than flittermouse

in dying light round darkened house

more silken-soft, more strange and fair

than slyphine maidens of the Air

whose wings in Varda's heavenly hall

in rhythmic movement heat and fall.

Down crumpled Orc, and Balrog proud;

all eyes were quenched, all heads were bowed;

the fires of heart and maw were stilled,

and ever like a bird she thrilled

above a lightless world forlorn

in ecstasy enchanted borne.

All eyes were quenched, save those that glared

in Morgoth's lowering brows, and stared

in slowly wandering wonder round,

and slow were in enchantment bound.

Their will wavered, and their fire failed,

and as beneath his brows they paled

the Silmarils like stars were kindled

that in the reek of Earth had dwindled

escaping upwards clear to shine,

glistening marvellous in heaven's mine.

Then flaring suddenly they fell,

down, down upon the floors of hell.

The dark and mighty head was bowed;

like mountain-top beneath a cloud

the shoulders foundered, the vast form

crashed, as in overwhelming storm

huge cliffs in ruin slide and fall;

and prone lay Morgoth in his hall.

His crown there rolled upon the ground,

a wheel of thunder; then all sound

died, and a silence grew as deep

as were the heart of Earth asleep.

Beneath the vast and empty throne

the adders lay like twisted stone,

the wolves like corpses foul were strewn;

and there lay Beren deep in swoon:

no thought, no dream nor shadow blind

moved in the darkness of his mind.

'Come forth, come forth! The hour hath knelled,

and Angband's mighty lord is felled!

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Geste of Beren and Lúthien

(Lines 4,044 to 4,115)

On Writing...

I am sure that some are born to write as trees are born to bear leaves: for these, writing is a necessary mode of their own development. If the impulse to write survives the hope of success, then one is among these. If not, then the impulse was at best only pardonable vanity, and it will certainly disappear when the hope is withdrawn.

C.S. Lewis to Arthur Greeves,

The Letters of C.S. Lewis, (28 August 1930)

The way for a person to develop a style is (a) to know exactly what he wants to say, and (b) to be sure he is saying exactly that. The reader, we must remember, does not start by knowing what we mean. If our words are ambiguous, our meaning will escape him. I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate open to the left or right the readers will most certainly go into it.

C.S. Lewis, God in the Dock,

"Cross-Examination" (1963)

Returning to work on an interrupted story is not like returning to work on a scholarly article. Fact, however long the scholar has left them untouched in his notebook, will still prove the same conclusions; he has only to start the engine running again. But the story is an organism: it goes on surreptitiously growing or decaying while your back is turned. If it decays, the resumption of work is like trying to coax back to life an almost extinguished fire, or to recapture the confidence of a shy animal which you had only partially tamed at your last visit.

C.S. Lewis, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century,

bk III.I (1954)

from "The Ascent of the Spear"

Taliessin walked in the palace yard;

he saw, under a guard, a girl sit in the stocks.

The stable-slaves, lounging by the gate,

cried catcalls and mocks, flung roots and skins of fruits.

She, rigid on the hard bench, disdained

motion, her cheek stained with a bruise, veined

with fury her forehead. The guard laughed and chaffed;

when Taliessin stepped near, he leapt to a rigid salute.

Lightly the king's poet halted, took the spear

from the manned hand, and with easy eyes dismissed.

Nor wist the crowd, he gone, what to do;

lifted arms fell askew; jaws gaped;

claws of fingers uncurled. They gazed,

amazed at the world of each inflexible head.

The silence loosened to speech; the king's poet said:

'Do I come as a fool? forgive folly; once more

be kind, be faithful: did we not together adore?

Say then what trick of temper or fate?' Hard-voiced,

she said without glancing, I sit here for taking a stick

to a sneering bastard slut, a Mongol ape,

that mouthed me in a wrangle.

Fortunate, for a brawl in the hall, to escape,

they dare tell me, the post, the stripping and whipping:

should I care, if the hazel rods cut flesh from bone?'

Charles Williams

Taliessin through Logres (1938)

Siamese cats...

[A Cambridge cat breeder had asked if she could register a litter of Siamese kittens under names taken from The Lord of the Rings.]

My only comment is that of Puck upon mortals. I fear that to me Siamese cats belong to the fauna of Mordor, but you need not tell the cat breeder that.

J.R.R. Tolkien

From a letter to Allen & Unwin

14 October 1959

My only comment is that of Puck upon mortals. I fear that to me Siamese cats belong to the fauna of Mordor, but you need not tell the cat breeder that.

J.R.R. Tolkien

From a letter to Allen & Unwin

14 October 1959

The first talk

The first talk in What Christians Believe dealt with alternative belief systems, with atheism and with pantheism. This was broadcast on 11 January 1942. When eventually published in the collected talks, better known as Mere Christianity, this first script was entitled The Rival Conceptions of God.

Lewis begins by telling the listener one thing that Christians do not have to believe. They don't have to believe that all other religions are entirely wrong. All can contain 'a hint of truth'. Atheists, on the other hand, have to believe that every religion has at its heart a massive mistake. Drawing on his own experience as someone who moved from atheism to theism and then to Christian conviction, Lewis admits that as a Christian he can be more liberal towards other religions than he could as an atheist. Although Christians maintain that what they believe is right and others are wrong, they can acknowledge that some answers, even wrong ones, can be closer to the right one than others. That's why those who believe in God are in a majority - atheism is harder than belief. And Lewis goes on to say that the one argument that most convinced him is the ability to think. If there is no creative intelligence behind the universe then his brain was not designed for thinking. If this was just a cosmic accident, he argues, using a brilliant illustration, 'it's like upsetting a milk jug and hoping that the way the splash arranges itself will give you a map of London'. How can one trust one's own thinking to be true?, he ponders. Lewis concludes: 'Unless I believe in God, I can't believe in thought: so I can never use thought to disbelieve in God.'

Justin Phillips

C.S. Lewis at the BBC

Gil-Galad

Bill Nighy singing my very favourite song from the 1980s. Written by J.R.R. Tolkien, I learned this at the time and have sung it many times as my 'party piece'. And now it turns up on You Tube. YES... THAT BILL NIGHY.

The tapes/CDs are really worth seeking out. Priceless... http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ngm9B9pYgy0 or click on the title above.

Tolkien on his critics in 1955

[The radio adaptation of The Lord of the Rings was discussed on the BBC programme 'The Critics'; and on 16 November, W. H. Auden gave a radio talk about the book in which he said: 'If someone dislikes it, I shall never trust their literary judgement about anything again.' Meanwhile Edwin Muir, reviewing The Return of the King in the Observer on 27 November, wrote: 'All the characters are boys masquerading as adult heroes .... and will never come to puberty. .... Hardly one of them knows anything about women.']

I agreed with the 'critics' view of the radio adaptation; but I was annoyed that after confessing that none of them had read the book they should turn their attention to it and me — including surmises on my religion. I also thought Auden rather bad – he cannot at any rate read verse, having a poor rhythmical sense; and deplored his making the book 'a test of literary taste'. You cannot do that with any work – and if you could you only infuriate. I was fully prepared for Roben Robinson's rejoinder 'fair-ground barker'. But I suppose all this is good for sales. My correspondence is now increased by letters of fury against the critics and the broadcast. One elderly lady – in part the model for 'Lobelia' indeed, though she does not suspect it – would I think certainly have set about Auden (and others) had they been in range of her umbrella. ....

I hope in this vacation to begin surveying the Silmarillion; though evil fate has plumped a doctorate thesis on me...

Blast Edwin Muir and his delayed adolescence. He is old enough to know better. It might do him good to hear what women think of his 'knowing about women', especially as a test of being mentally adult. If he had an M.A. I should nominate him for the professorship of poetry – a sweet revenge.

Letter to Rayner Unwin

8 December 1955

J.R.R. Tolkien

A tame sort of God?

One reason why many people find Creative Evolution so attractive is that it gives one much of the emotional comfort of believing in God and none of the less pleasant consequences. When you are feeling fit and the sun is shining and you do not want to believe that the whole universe is a mere mechanical dance of atoms, it is nice to be able to think of this great mysterious Force rolling on through the centuries and carrying you on its crest. If, on the other hand, you want to do something rather shabby, the Life Force, being only a blind force, with no morals and no mind, will never interfere with you like that troublesome God we learned about when we were children. The Life Force is a sort of tame God. You can switch it on when you want, but it will not bother you. All the thrills of religion and none of the cost. Is the Life Force the greatest achievement of wishful thinking the world has yet seen?

C.S. Lewis

‘Mere Christianity’

Clarity or Obscurity?

The pattern of divided knowledge can be traced in criticisms of Charles Williams' writings. C.S. Lewis, himself a model of clarity, 'pitched into' Williams for all he was worth for his “obscurity”. Some think he writes ‘purple prose’, others that he writes a kind of shorthand. For some his style is too highly coloured, and some can't make head or tail of him! One couple to whom, with greater enthusiasm than judgement, I lent War in Heaven, returned it half-read with barely suppressed shudders, murmuring misgivings over his - and probably my! - preoccupation with the occult.

At our meeting in February 1986, Dr Rowan Williams described certain excerpts from The Descent of the Dove as 'purple passages’ and some of C.W.'s writings as self-indulgent. Charles Williams, interestingly enough, makes a similar observation of St Paul: “There must have been many of the churches he founded who were so illiterate as not to have heard of his best purple passages.” It seems Williams is in good company; and purple is, of course, a royal colour. Hugo Epson's exclamation: ‘clotted glory from Charles!’ will find an echo in many of C.W.'s readers. There is certainly lots of glory. Sometimes he seems almost too highly coloured - and charged! - for us to swallow. Eternity and eternal truths are so richly described, almost laid on with a trowel , that the effect can be akin to being faced with a rich and creamy dessert after a full and satisfying first course. Like the man who, having begged God for a revelation, got what he asked for, one wants to cry; ‘0 enough! enough! I can't bear any more!' There is just so much of the beatific vision mortal man can bear, and live, even when despite its brilliance, it is a veiled splendour.

Joan Northam

Charles Williams Society Newsletter

No 45 - Spring 1987 (excerpt)

Love making in Modern Literature

Wayland Young:

Wayland Young:… in general from the standpoint of Christian morality, the description of love-making in literature is on a par with the description of anything else, or less so?

CS Lewis:

Well, I think the description of any immoral action whether in the sexual sphere or any other, if so contrived as to produce a tendency to that action in the mind of the reader, I would condemn. Though whether I would impose my Christian condemnation through the law for non-Christian fellow citizens is quite a different matter.

Wayland Young:

Supposing it's not an immoral action, supposing it's between husband and wife? And yet is described very vividly?

CS Lewis:

Well, I suppose one thinks there that this sort of thing tends to lead to masturbation on the part of the young reader, but perhaps one ought to say rather that it should be kept away from the young reader. That it ought to be kept away from everyone, I really just don't know. I don't think it's likely to be very [good?] art because, as I said earlier, I don't think some things can be, as in Wordsworth's phrase, recollected in tranquillity, and also, stimulation of this particular impulse does not really seem to be very necessary.

Wayland Young:

Well, the next thing is, of course, is masturbation a wrong action?

CS Lewis:

Well, I think I would say to that unless you hold, as I do hold, the specifically Christian view of the human body, I'm not very clear that it is morally wrong. It may be bad as it incapacitates a person, and I don't mean physically, but psychologically incapacitating him for real love affairs, but I don't know - I'm only guessing there.

C.S. Lewis

Interview with Wayland Young (19 Jan 1962)

Journal of Inklings Studies (Vol 1 No 1)

The spark that lit the fire

(Charles) would admit that he was not a tidy man in the office and had occasional clean-ups. On one such occasion, after one paper basket was full he turned out a large typescript which he said could go as it had been refused by all the publishing houses. I said what a pity. He shrugged and said that I could do what I liked with it. So I sent it to Victor Gollancz who had recently started publishing. It was accepted and appeared with the title War in Heaven. The following is an example of his generosity. One day he called me into his office, opened a parcel, took out the first copy of War in Heaven, inscribed it "The spark that lit the fire" and handed it to me. He said then that poetry was his first love, but novels would be bread and butter.

Jo Harris

“Charles Williams as I knew Him”

(Charles Williams Society Newsletter) No 4 - Winter 1976 (excerpt)

Most interesting… so here’s the first page of the novel, published in 1930:

Chapter One (The Prelude)

The telephone bell was ringing wildly, but without result, since there was no-one in the room but the corpse.

A few moments later there was. Lionel Rackstraw, strolling back from lunch, heard in the corridor the sound of the bell in his room, and, entering at a run, took up the receiver. He remarked, as he did so, the boots and trousered legs sticking out from the large knee-hole table at which he worked, but the telephone had established the first claim on his attention.

"Yes," he said, "yes... No, not before the 17th... No, who cares what he wants?... No, who wants to know?... Oh, Mr. Persimmons. Oh, tell him the 17th... Yes... Yes, I'll send a set down."

He put the receiver down and looked back at the boots.

It occurred to him that someone was probably doing something to the telephone; people did, he knew, at various times drift in on him for such purposes. But they usually looked round or said something; and this fellow must have heard him talking. He bent down towards the boots.

"Shall you be long?" he said into the space between the legs and the central top drawer; and then, as there was no answer, he walked away, dropped hat and gloves and book on to their shelf, strolled back to his desk, picked up some papers and read them, put them back, and, peering again into the dark hole, said more impatiently, "Shall you be long?"

No voice replied; not even when, touching the extended foot with his own, he repeated the question. Rather reluctantly he went round to the other side of the table, which was still darker, and, trying to make out the head of the intruder, said almost loudly: "Hallo! hallo! What's the idea?" Then, as nothing happened, he stood up and went on to himself: "Damn it all, is he dead?" and thought at once that he might be.

Charles Williams

War In Heaven

War In Heaven

from "The English Poets"

Every great nation has expressed its spirit in art: generally in some particular form of art. The Italians are famous for their painting, the Germans for their music, the Russians for their novels. England is distinguished for her poets. A few of these, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, are acknowledged to be among the supreme poets of the world. But there are many others besides these. Shakespeare is only the greatest among an array of names. Seven or eight other English poets deserve world-wide fame: in addition to them, many others in every age have written at least one poem that has made them immortal. The greatness of English poetry has been astonishingly continuous. German music and Italian painting flourished, at most, for two hundred years. England has gone on producing great poets from the fourteenth century to to-day: there is nothing like it in the history of the arts.

That the English should have chosen poetry as the chief channel for their artistic talent is the result partly of their circumstances, partly of their temperament.

English is a poet's language. It is ideally suited for description or for the expression of emotion. It is flexible, it is varied, it has an enormous vocabulary; able to convey every subtle diverse shade, to make vivid before the mental eye any picture it wishes to conjure up. Moreover its very richness helps it to evoke those indefinite moods, those visionary flights of fancy of which so much of the material of poetry is composed. There is no better language in the world for touching the heart and setting the imagination aflame.

English poetry has taken full advantage of its possibilities. Circumstances have helped it. Nature placed England in the Gothic North, the region of magic and shadows, of elves and ghosts, and romantic legend. But from an early period she has been in touch with classic civilisation, with its culture, its sense of reality, its command of form. In consequence her poetry has got the best of two traditions. On the whole Nature has been a stronger influence than history. Most good English poets have been more Gothic than classical; inspired but unequal, memorable for their power to suggest atmosphere and their flashes of original beauty, rather than for their clear design, or their steady level of good writing. For the most part too, they write spontaneously, without reference to established rules of art. But they have often obeyed these rules, even when they were not conscious of them: and some, Milton and Chaucer for instance, are as exact in form and taste as any Frenchman. No generalisation is uniformly true about English poetry. It spreads before us like a wild forest, a tangle of massive trees and luxuriantly-flowering branches, clamorous with bird song: but here and there art has cut a clearing in it and planted a delicate formal garden.

Lord David Cecil

Collins 1942

The Death of Charles Williams

[The King's Arms on the junction of Parks Road & Holywell Street, Oxford]

Tuesday 15th May, 1945.

At 12.50 this morning… the telephone rang, and a woman's voice asked if I would take a message for J — "Mr. Charles Williams died in the Acland this morning". One often reads of people being "stunned" by bad news, and reflects idly on the absurdity of the expression; but there is more than a little truth in it. I felt just as if I had slipped and come down on my head on the pavement. J had told me when I came into College that Charles was ill, and it would mean a serious operation: and then went off to see him: I haven't seen him since. I felt dazed and restless, and went out to get a drink: choosing unfortunately the King's Arms, where during the winter Charles and I more than once drank a pint after leaving Tollers at the Mitre, with much glee at "clearing one throats of varnish with good honest beer": as Charles used to say.

There will be no more pints with Charles: no more "Bird and Baby": the blackout has fallen, and the Inklings can never be the same again. I knew him better than any of the others, by virtue of his being the most constant attendant. I hear his voice as I write, and can see his thin form in his blue suit, opening his cigarette box with trembling hands. These rooms will always hold his ghost for me. There is something horrible, something unfair about death, which no religious conviction can overcome. "Well, goodbye, see you on Tuesday Charles" one says — and you have in fact though you don't know it, said goodbye for ever. He passes up the lamplit street, and passes out of your life for ever.

There is a good deal of stuff talked about the horrors of a lonely old age; I'm not sure that the wise man — the wise materialist at any rate — isn't the man who has no friends. And so vanishes one of the best and nicest men it has ever been my good fortune to meet. May God receive him into His everlasting happiness.

Warren (Warnie) Lewis

Brothers & Friends (Harper & Row 1982)

Bors and Elayne: The King’s Coins

The king has set up his mint by Thames.

He has struck coins; his dragon's loins

germinate a crowded creaturely brood

to scuttle and scurry between towns and towns,

to furnish dishes and flagons with change of food;

small crowns, small dragons, hurry to the markets

under the king's smile, or flat in houses squat.

The long file of their snout crosses the empire,

and the other themes acknowledge our king's head.

They carry on their backs little packs of value,

caravans; but I dreamed the head of a dead king

was carried on all, that they teemed on house-roofs

where men stared and studied them as I your thumbs' epigrams,

hearing the City say Feed my lambs

to you and the king; the king can tame dragons to carriers,

but I came through the night, and saw the dragonlets' eyes

leer and peer, and the house-roofs under their weight

creak and break; shadows of great forms

halloed them on, and followed over falling towns.

I saw that this was the true end of our making;

mother of children, redeem the new law.

Taliessin's look darkened; his hand shook

while he touched the dragons; he said 'We had a good thought.

Sir, if you made verse you would doubt symbols.

I am afraid of the little loosed dragons.

When the means are autonomous, they are deadly; when words

escape from verse they hurry to rape souls;

when sensation slips from intellect, expect the tyrant;

the brood of carriers levels the good they carry.

We have taught our images to be free; are we glad?

are we glad to have brought convenient heresy to Logres?

Charles Williams ~ ‘Bors to Elayne: on the King’s Coins’

Arthurian Poets (The Boydell Press) 1991 (extract)

What is the Purpose of Life?

[Rayner Unwin's daughter Camilla was told, as part of a school 'project', to write and ask: 'What is the purpose of life?']

20 May 1969 [19 Lakeside Road, Branksome Park, Poole]

Dear Miss Unwin,

I am sorry my reply has been delayed. I hope it will reach you in time. What a very large question! I do not think 'opinions', no matter whose, are of much use without some explanation of how they are arrived at; but on this question it is not easy to be brief.

What does the question really mean? Purpose and Life both need some definition. Is it a purely human and moral question; or does it refer to the Universe? It might mean: How ought I to try and use the life-span allowed to me? OR: What purpose/design do living things serve by being alive? The first question, however, will find an answer (if any) only after the second has been considered.

I think that questions about 'purpose' are only really useful when they refer to the conscious purposes or objects of human beings, or to the uses of things they design and make. As for 'other things' their value resides in themselves: they ARE, they would exist even if we did not. But since we do exist one of their functions is to be contemplated by us. If we go up the scale of being to 'other living things', such as, say, some small plant, it presents shape and organization: a 'pattern' recognizable (with variation) in its kin and offspring; and that is deeply interesting, because these things are 'other' and we did not make them, and they seem to proceed from a fountain of invention incalculably richer than our own.

Human curiosity soon asks the question HOW: in what way did this come to be? And since recognizable 'pattern' suggests design, may proceed to WHY? But WHY in this sense, implying reasons and motives, can only refer to a MIND. Only a Mind can have purposes in any way or degree akin to human purposes. So at once any question:

'Why did life, the community of living things, appear in the physical Universe?' introduces the Question: Is there a God, a Creator-Designer, a Mind to which our minds are akin (being derived from it) so that It is intelligible to us in part. With that we come to religion and the moral ideas that proceed from it. Of those things I will only say that 'morals' have two sides, derived from the fact that we are individuals (as in some degree are all living things) but do not, cannot, live in isolation, and have a bond with all other things, ever closer up to the absolute bond with our own human kind.

So morals should be a guide to our human purposes, the conduct of our lives: (a) the ways in which our individual talents can be developed without waste or misuse; and (b) without injuring our kindred or interfering with their development. (Beyond this and higher lies self-sacrifice for love.)

But these are only answers to the smaller question. To the larger there is no answer, because that requires a complete knowledge of God, which is unattainable. If we ask why God included us in his Design, we can really say no more than because He Did.

If you do not believe in a personal God the question: 'What is the purpose of life?' is unaskable and unanswerable. To whom or what would you address the question? But since in an odd corner (or odd corners) of the Universe things have developed with minds that ask questions and try to answer them, you might address one of these peculiar things. As one of them I should venture to say (speaking with absurd arrogance on behalf of the Universe): 'I am as I am. There is nothing you can do about it. You may go on trying to find out what I am, but you will never succeed. And why you want to know, I do not know. Perhaps the desire to know for the mere sake of knowledge is related to the prayers that some of you address to what you call God. At their highest these seem simply to praise Him for being, as He is, and for making what He has made, as He has made it.'

Those who believe in a personal God, Creator, do not think the Universe is in itself worshipful, though devoted study of it may be one of the ways of honouring Him. And while as living creatures we are (in part) within it and part of it, our ideas of God and ways of expressing them will be largely derived from contemplating the world about us. (Though there is also revelation both addressed to all men and to particular persons.)

So it may be said that the chief purpose of life, for any one of us, is to increase according to our capacity our knowledge of God by all the means we have, and to be moved by it to praise and thanks. To do as we say in the Gloria in Excelsis: Laudamus te, benedicamus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te, gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam. We praise you, we call you holy, we worship you, we proclaim your glory, we thank you for the greatness of your splendour.

And in moments of exaltation we may call on all created things to join in our chorus, speaking on their behalf, as is done in Psalm 148, and in The Song of the Three Children in Daniel II. PRAISE THE LORD ... all mountains and hills, all orchards and forests, all things that creep and birds on the wing. This is much too long, and also much too short – on such a question.

With best wishes

J. R. R. Tolkien.

(Letter to Camilla Unwin)

The Full Treatment

When I was a child I often had toothache, and I knew that if I went to my mother she would give me something which would deaden the pain for that night and let me get to sleep. But I did not go to my mother -- at least, not till the pain became very bad. And the reason I did not go was this. I did not doubt she would give me the aspirin; but I knew she would also do something else. I knew she would take me to the dentist next morning. I could not get what I wanted out of her without getting something more, which I did not want. I wanted immediate relief from pain: but I could not get it without having my teeth set permanently right. And I knew those dentists: I knew they started fiddling about with all sorts of other teeth which had not yet begun to ache. They would not let sleeping dogs lie, if you gave them an inch they took an ell.

Now, if I may put it that way, Our Lord is like the dentists. If you give Him an inch, He will take an ell. Dozens of people go to Him to be cured of some one particular sin which they are ashamed of or which is obviously spoiling daily life. Well, He will cure it all right: but He will not stop there. That may be all you asked; but if once you call Him in, He will give you the full treatment.

C.S. Lewis

Mere Christianity

The Eagle and Child

When I'm in Oxford I often go there for lunch - they do a decent pub lunch. The Eagle & The Child is on the west side of the Woodstock Road just as the Banbury Road is forking off of hit, about 1/2 mile north of the city center. They have a lovely display of photos of the Inklings but they'd done some remodeling the last time I was there...

An English pub is quite different from an American bar - I don't think we have anything equivalent. It's a "public house" - they often serve very good food (but, as above, re: Bird & Baby, lunch is served in a narrow window of "lunch" hours - you can't get "lunch" at 4 p.m. and I don't think they do dinner...) and they serve as a community meeting place. I'm sure some folks get drunk there but I've never seen it. The British do drink more than the Americans, just in general, but there are nice things you can drink which are non-alcoholic. Or you might try cider, which is slightly alcoholic (if you can call 7º 'slightly alcoholic' - Ed.) and you can get it sweet or dry (personally, I prefer the dry) - you can get a rather interesting drink called "shandy" which is half beer (lager or ale) and half lemonade - but don't worry! Their "lemonade" is what we call Seven-up!!! (an Englishman would argue about that - Ed) It's rather nice.

Some pubs are better/nicer than others, some are downright posh. But the Eagle and Child is rather homey in a very pleasant way, not dank at all. There are two front rooms (you enter through a hallway between them) one has a fireplace, then the ordering area (you go up to the "bar" and give your order; look around for the chalkboard with the food specials on it), then it continues to the back and they've added some rooms to it, so it's larger than it used to be.

Lynn Maudlin

Influences...

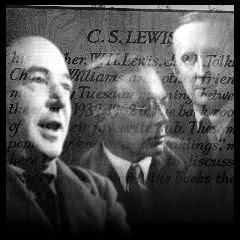

I don't think Tolkien influenced me*, and I am certain that I didn't influence him. That is, didn't influence what he wrote. My continual encouragement, carried to the point of nagging, influenced him very much to write at all with that gravity and at that length. In other words I acted as a midwife not as a father. The similarities between his work and mine are due, I think, (a) To nature - temperament. (b) to common sources. We are both soaked in Norse mythology, George MacDonald's fairy-tales, Homer, Beowulf, and medieval romance. Also, of course, we are both Christians (he, an R.C.).

The relevance of your problem to 'Higher Criticism' is extremely important. Reviewers of his books and mine, both friendly & hostile, constantly put forward imaginary histories of their composition. I do not think any one of these has ever borne the slightest resemblance to the real history. (e.g. they think his deadly Ring is a symbol of the atom bomb. Actually his myth was developed long before the atom bomb had been heard of).

You see the moral. These critics, in dealing with us, have every advantage which modern scholars lack in dealing with Scripture. They are dealing with authors who have the same mother tongue, the same education, and inhabit the same social & political world as their own, and inherit the same literary traditions. In spite of this, when they tell us how the books were written they are all wildly wrong! After that what chance can there be that any modern scholar can determine how Isaiah or the Fourth Gospel [...] came into existence? I should put the odds at 10,000 to 1 against you all. [...]

The Narnian series is not exactly allegory. I'm not saying 'Let us represent in terms of märchen** the actual story of this world.' Rather 'Supposing the Narnia world, let us guess what form the activities of the Second Person or Creator, Redeemer, and Judge might take there.' This, you see, overlaps with allegory but is not quite the same.

I don't think a marsh-wiggle is like a hobbit. The hobbit is essentially a cheerful, complacent, sanguine little creature. If Puddeglum is like any of Tolkien's characters, I'd call him 'a good Gollum'.

C.S. Lewis

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis: Volume III

Letter to Francis Anderson 23 Sept 1963

_______________________

* Anderson had written to Lewis asking what the connection was between the Lord of the Rings and the Narnia series and which writer had influenced the other.

**märchen - the German term for tales of enchantment and marvels, usually translated as ‘fairy tales’.

Looking for the King

"What is this Holy Grail we hear so much about?" asked Williams, pacing back and forth so rapidly that Tom could hear keys or coins clinking in his pocket. "Is the Grail the holy chalice used by Jesus on the night of the Last Supper? Is it a cup in which Joseph of Arimathea caught drops of Christ's blood as he was stretched out on the cross?" Again, Williams peered into individual faces, speaking to over a hundred people, but giving each one the impression he was talking just to him. "Or perhaps you favor the Loomis school: the Grail is a bit of 'faded mythology', a Celtic cauldron of plenty that somehow got lugged into Arthurian lore?"

Williams paced back and forth some more, throwing his hands into the air, as if to say, who can answer all these imponderable questions? Then he plunged in again: "There is no shortage of texts on the subject. Let's start with Chretien de Troyes: Percival, or the Story of the Grail, written sometime in the 1180s. This is the first known account of the Grail. The young knight Percival sits at banquet at the castle Carbonek and sees an eerie procession—a young man carrying a bleeding lance, two boys with gold candelabra, then finally a fair maid with a jeweled grail, a platter bearing the wafer of the Holy Mass. Percival doesn't ask what it all means and thereby brings a curse upon himself and on the land." Williams surveyed the crowd again, as if waiting for someone to stand and explain all this to him. The room was silent as a church at midnight, so Williams went on, listing all the famous medieval texts and their retellings of the Grail legend, noting how their dates clustered around the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.

"So much for the literary versions", he continued. "But what is this Grail really"? What lies behind the texts? Some describe it as a cup or bowl, some as a stone, some as a platter. The word grail, by the way, comes from the Latin gradalis, more like a shallow dish, or a paten, than a chalice." After another strategic pause, Williams exclaimed, almost in a shout, "How extraordinary! Here we have what some would call the holiest relic in Christendom, and no one seems to know what it looks like."

Pacing some more, as if trying to work off an excess of agitation and intellectual energy, Williams went back to the lectern and leaned on it heavily…

David C. Downing

Looking for the King (Chapter 3)

Ignatius Press 2010

Faith? Or Good Works?

The Bible really seems to clinch the matter when it puts the two things together into one amazing sentence. The first half is, 'Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling' - which looks as if everything depended on us and our good actions; but the second half goes on, 'For it is God who worketh in you' - which looks as if God did everything and we nothing.

I am afraid that is the sort of thing we come up against in Christianity. I am puzzled, but I am not surprised. You see, we are now trying to understand, and to separate into water-tight compartments, what exactly God does and what man does when God and man are working together. And, of course, we begin by thinking it is like two men working together, so that you could say , 'He did this bit and I did that.' But this way of thinking breaks down. God is not like that. He is inside you as well as outside: even if we could understand who did what, I do not think human language could properly express it. In the attempt to express it different Churches say different things. But you will find that even those who insist most strongly on the importance of good actions tell you you need Faith; and even those who insist most strongly on Faith tell you to do good actions. At any rate that is as far as I can go.

C.S. Lewis

'Mere Christianity' (1952)

The Kilns in Wartime

In the First World War two things had been invented which were to change the whole face of wartime life for the people living at home. One was airplanes that could fight; as well as transport bombers and fighters. The other was submarines. Bombers now allowed the vileness of war to be brought from the battlefields right into the cities and homes of the civilian populations of the warring nations. Submarines had been used to sink warships, but in this new war they were being used to sink merchant ships in an effort to starve the people of Britain into surrender.

So the first thing that had to be done was to protect the children of the cities from the danger of being blown to bits by bombs dropped from the sky. In England, children from London and other cities were evacuated to country areas, and soon several schoolgirls were living at The Kilns. Paxford and lack had built and buried a concrete air-raid shelter up by the lake (it's still there; and if you walk from the house up to the lake, turn left, and work your way through the overgrown bushes, you will find it), and the house had to be fitted with black-out curtains so that at night no slightest gleam of light could escape the windows to attract the interest of enemy pilots. These were heavy curtains often made out of thick wool blankets of the same kind as were issued to soldiers or sailors in the armed forces. Air raid protection (ARP) wardens were appointed to walk around on patrol at night, and the cry of, "Oi! Number 27, dowse that glim!" and the like were often to be heard as the warden spotted a gleam of light from the windows of number 27 of whatever street he was patrolling at the time.

At The Kilns, at first the blackout was achieved by a whole conglomeration of towels, rags, spare clothes, blankets, and all sorts of weird and wonderful bits and pieces, but eventually, heavy navy blue and khaki (of the English olive green sort) blankets were tailored to fit the windows, and only the last chinks were filled with odds and ends of material to seal in the light. They also helped to keep the cold out, and this was important because all the coal, which was the main fuel burned in the fireplaces and boilers for heating, was soon to be needed for running the steam engines of ships and trains. Coal for household use became hard to get.

Douglas Gresham

'Jack's Life' (Broadman & Holman) 2005

The Images

Henry took a few steps forward, slowly and softly, almost as if he were afraid that those small images would overhear him, and softly and slowly Aaron followed. They paused at a little distance from the table, and stood gazing at the figures, the young man in a careful comparison of them with his memory of the newly found cards. He saw among them those who bore the coins, and those who held swords or staffs or cups; and among those he searched for the shapes of the Greater Trumps, and one by one his eyes found them, but each separately, so that as he fastened his attention on one the rest faded around it to a golden blur.

But there they were, in exact presentation--the juggler who danced continuously round the edge of the circle, tossing little balls up and catching them again; the Emperor and Empress; the masculine and feminine hierophants; the old anchorite treading his measure and the hand-clasped lovers wheeling in theirs; a Sphinx-drawn chariot moving in a dancing guard of the four lesser orders; an image closing the mouth of a lion, and another bearing a cup closed by its hand, and another with scales but with unbandaged eyes--which had been numbered in the paintings under the titles of strength and temperance and justice; the wheel of fortune turning between two blinded shapes who bore it; two other shapes who bore between them a pole or cross on which hung by his foot the image of a man; the swift ubiquitous form of a sickle-armed Death; a horned mystery bestriding two chained victims; a tower that rose and fell into pieces, and then was re-arisen in some new place; and the woman who wore a crown of stars, and the twin beasts who had each of them on their heads a crescent moon, and the twin children on whose brows were two rayed suns in glory--the star, the moon, the sun; the heavenly form of judgement who danced with a skeleton half freed from its graveclothes, and held a trumpet to its lips; and the single figure who leapt in a rapture and was named the world.

One by one Henry recognized them and named them to himself, and all the while the tangled measure went swiftly on. After a few minutes he looked round: "They're certainly the same; in every detail they're the same. Some of the attributed meanings aren't here, of course, but that's all."

Charles WilliamsBut there they were, in exact presentation--the juggler who danced continuously round the edge of the circle, tossing little balls up and catching them again; the Emperor and Empress; the masculine and feminine hierophants; the old anchorite treading his measure and the hand-clasped lovers wheeling in theirs; a Sphinx-drawn chariot moving in a dancing guard of the four lesser orders; an image closing the mouth of a lion, and another bearing a cup closed by its hand, and another with scales but with unbandaged eyes--which had been numbered in the paintings under the titles of strength and temperance and justice; the wheel of fortune turning between two blinded shapes who bore it; two other shapes who bore between them a pole or cross on which hung by his foot the image of a man; the swift ubiquitous form of a sickle-armed Death; a horned mystery bestriding two chained victims; a tower that rose and fell into pieces, and then was re-arisen in some new place; and the woman who wore a crown of stars, and the twin beasts who had each of them on their heads a crescent moon, and the twin children on whose brows were two rayed suns in glory--the star, the moon, the sun; the heavenly form of judgement who danced with a skeleton half freed from its graveclothes, and held a trumpet to its lips; and the single figure who leapt in a rapture and was named the world.

One by one Henry recognized them and named them to himself, and all the while the tangled measure went swiftly on. After a few minutes he looked round: "They're certainly the same; in every detail they're the same. Some of the attributed meanings aren't here, of course, but that's all."

The Greater Trumps

(Ch. 2 The Hermit)

Another Aesthetic Experience

When I was fourteen I went walking in the park on a Sunday afternoon, in clean, cold, luminous air. The trees tinkled with sleet; the city noises were muffled by the snow. Winter sunset, with a line of young maples sheathed in ice between me and the sun—as I looked up they burned unimaginably golden—burned and were not consumed. I heard the voice in the burning tree; the meaning of all things was revealed and the sacrament at the heart of all beauty lay bare; time and space fell away, and for a moment the world was only a door swinging ajar. Then the light faded, the cold stung my toes, and I went home, reflecting that I had had another aesthetic experience. I had them fairly often. That was what beautiful things did to you, I recognized, probably because of some visceral or glandular reaction that hadn't been fully explored by science just yet. For I was a well-brought-up, right-thinking child of materialism. Beauty, I knew, existed; but God, of course, did not .... A young poet like myself could be seized and shaken by spiritual powers a dozen times a day, and still take it for granted that there was no such thing as spirit. (Davidman's emphasis)

When I was fourteen I went walking in the park on a Sunday afternoon, in clean, cold, luminous air. The trees tinkled with sleet; the city noises were muffled by the snow. Winter sunset, with a line of young maples sheathed in ice between me and the sun—as I looked up they burned unimaginably golden—burned and were not consumed. I heard the voice in the burning tree; the meaning of all things was revealed and the sacrament at the heart of all beauty lay bare; time and space fell away, and for a moment the world was only a door swinging ajar. Then the light faded, the cold stung my toes, and I went home, reflecting that I had had another aesthetic experience. I had them fairly often. That was what beautiful things did to you, I recognized, probably because of some visceral or glandular reaction that hadn't been fully explored by science just yet. For I was a well-brought-up, right-thinking child of materialism. Beauty, I knew, existed; but God, of course, did not .... A young poet like myself could be seized and shaken by spiritual powers a dozen times a day, and still take it for granted that there was no such thing as spirit. (Davidman's emphasis)Joy Davidman

'The Longest Way Round' (1951)

rep. 'Journal of Inkling Studies' Vol 1 No 1 (March 2011)

Amon Rudh

Then suddenly there was a rock-wall before them, flat-faced and sheer, forty feet high, maybe, but dusk dimmed the sky above them and guess was uncertain.

'Is this the door of your house?' said Turin. 'Dwarves love stone, it is said.' He drew close to Mim, lest he should play them some trick at the last.

'Not the door of the house, but the gate of the garth,' said Mim. Then he turned to the right along the cliff-foot, and after twenty paces he halted suddenly; and Turin saw that by the work of hands or of weather there was a cleft so shaped that two faces of the wall overlapped, and an opening ran back to the left between them. Its entrance was shrouded by long trailing plants rooted in crevices above, but within there was a steep stony path going upward in the dark. Water trickled down it, and it was dank.

One by one they filed up. At the top the path turned right and south again, and brought them through a thicket of thorns out upon a green flat, through which it ran on into the shadows. They had come to Mim's house, Bar-en-Nibin-noeg, which only ancient tales in Doriath and Nar-gothrond remembered, and no Men had seen. But night was falling, and the east was starlit, and they could not yet see how this strange place was shaped.

Amon Rudh had a crown: a great mass like a steep cap of stone with a bare flattened top. Upon its north side there stood out from it a shelf, level and almost square, which could not be seen from below; for behind it stood the hill-crown like a wall, and west and east from its brink sheer cliffs fell. Only from the north, as they had come, could it be reached with ease by those who knew the way.

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Children of Húrin

Chapter VII - 'Of Mîm the Dwarf'

[Image: Ted Nasmith]

Flat-earthers, and 'kindly enclyning'

Physically considered, the Earth is a globe; all the authors of the high Middle Ages are agreed on this. In the earlier 'Dark' Ages, as indeed in the nineteenth century, we can find Flat-earthers. Lecky, whose purpose demanded some denigration of the past, has gleefully dug out of the sixth century Cosmas Indicopleustes who believed the Earth to be a flat parallelogram. But on Lecky's own showing Cosmas wrote partly to refute, in the supposed interests of religion, a prevalent, contrary view which believed in the Antipodes. Isidore gives Earth the shape of a wheel. And Snorre Sturlason thinks of it as the 'world-disc' or heimskringla --the first word, and hence the title, of his great saga. But Snorre writes from within the Norse enclave which was almost a separate culture, rich in native genius but half cut off from the Mediterranean legacy which the rest of Europe enjoyed.

The implications of a spherical Earth were fully grasped. What we call gravitation--for the medievals 'kindly enclyning'--was a matter of common knowledge. Vincent of Beauvais expounds it by asking what would happen if there were a hole bored through the globe of Earth so that there was a free passage from the one sky to the other, and someone dropped a stone down it. He answers that it would come to rest at the centre. [...]The most vivid presentation is by Dante, in a passage which shows that intense realising power which in the medieval imagination oddly co-exists with its feebleness in matters of scale. In Inferno, XXXIV, the two travellers find the shaggy and gigantic Lucifer at the absolute centre of the Earth, embedded up to his waist in ice. The only way they can continue their journey is by climbing down his sides--there is plenty of hair to hold on by--and squeezing through the hole in the ice and so coming to his feet. But they find that though it is down to his waist, it is up to his feet. As Virgil tells Dante, they have passed the point towards which all heavy objects move. It is the first 'science-fiction effect' in literature.

C.S. Lewis

The Discarded Image, "Earth and her Inhabitants" (1964)

Doppelgaenger...

Her heart sprang; there, a good way off-thanks to a merciful God - it was, materialized from nowhere in a moment. She knew it at once, however far, her own young figure, her own walk, her own dress and hat-had not her first sight of it been attracted so? changing, growing.... It was coming up at her pace - doppelgaenger, doppelgaenger - her control began to give... two... she didn't run, lest it should, nor did it. She reached her gate, slipped through, went up the path. If it should be running very fast up the road behind her now? She was biting back the scream and fumbling for her key. Quiet, quiet! "A terrible good." She got the key into the keyhole; she would not look back; would it click the gate or not? The door opened; and she was in, and the door banged behind her. She all but leant against it, only the doppelgaenger might be leaning similarly on the other side. She went forward, her hand at her throat, up the stairs to her room, desiring (and every atom of energy left denying that her desire could be vain) that there should be left to her still this one refuge in which she might find shelter.

Charles Williams

Descent into Hell

(Ch. 1 - The Magnus Zoroaster)

An unliterary man

An unliterary man may be defined as one who reads books once only...

The re-reader is looking not for actual surprises (which can come only once) but for a certain surprisingness... It is the quality of unexpectedness, not the fact that delights us. It is even better the second time...in literature. we do not enjoy a story fully at the first reading. Not till the curiosity, the sheer narrative lust, has been given its sop and laid asleep, are we at leisure to savour the real beauties. Til then, it is like wasting great wine on a ravenous natural thirst which merely wants cold wetness. The children understand this well when they ask for the same story over and over again, and in the same words. They want to have again the "surprise" of discovering that what seemed Little-Red-Riding-Hood's grandmother is really the wolf. It is better when you know it is coming: free from the shock of actual surprise you can attend better to the intrinsic surprisingness of the peripeteia*.

C.S. Lewis, Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, "On Stories" (1947)

* peripeteia: A sudden change of events or reversal of circumstances, especially in a literary work.

Of Fingolfin and Morgoth (Last)

Halt goes for ever from that stroke

great Morgoth; but the king he broke,

and would have hewn and mangled thrown

to wolves devouring. Lo! From throne

that Manwë bade him build on high,

on peak unscaled beneath the sky,

Morgoth to watch, now down there swooped

Thorndor the King of Eagles, stooped,

and rending beak of gold he smote

in Bauglir's face, then up did float

on pinions thirty fathoms wide

bearing away, though loud they cried,

the mighty corse, the Elven-king;

and where the mountains make a ring

far to the south about that plain

where after Gondolin did reign,

embattled city, at great height

upon a dizzy snowcap white

in mounded cairn the mighty dead

he laid upon the mountain's head.

Never Orc nor demon after dared

that pass to climb, o'er which there stared

Fingolfin's high and holy tomb,

till Gondolin's appointed doom.

(lines 3,608 to 3,631)

The Geste of Beren and Lúthien

J.R.R. Tolkien

[Image: Ted Naismith]

Of Fingolfin and Morgoth (IV)

Thrice was Fingolfin with great blows

to his knees beaten, thrice he rose

still leaping up beneath the cloud

aloft to hold star-shining, proud,

his stricken shield, his sundered helm,

the dark nor might could overwhelm

till all the earth was burst and rent

in pits about him. He was spent.

His feet stumbled. He fell to wreck

upon the ground, and on his neck

a foot like rooted hills was set,

and he was crushed—not conquered yet;

one last despairing stroke he gave:

the mighty foot pale Ringil clave

about the heel, and black the blood

gushed as from smoking fount in flood.

(lines 3,592 to 3,607)

The Geste of Beren and Lúthien

J.R.R. Tolkien

[Image: Antti Autio]

Of Fingolfin and Morgoth (III)

Fingolfin like a shooting light

beneath a cloud, a stab of white,

sprang then aside, and Ringil drew

like ice that gleameth cold and blue,

his sword devised of elvish skill

to pierce the flesh with deadly chill.

With seven wounds it rent his foe,

and seven mighty cries of woe

rang in the mountains, and the earth quook,

and Angband's trembling armies shook.

Yet Orcs would after laughing tell

of the duel at the gates of hell;

though elvish song thereof was made

ere this but one—when sad was laid

the mighty king in barrow high,

and Thorndor, Eagle of the sky,

the dreadful tidings brought and told

to mourning Elfinesse of old.

(lines 3,574 to 3,591)

The Geste of Beren and Lúthien

J.R.R. Tolkien

[Image: Ted Nasmith]

Of Fingolfin and Morgoth (II)

[Image: Ted Nasmith]

Then Morgoth came. For the last time

in those great wars he dared to climb

from subterranean throne profound,

the rumour of his feet a sound

of rumbling earthquake underground.

Black-armoured, towering, iron-crowned

he issued forth; his mighty shield

a vast unblazoned sable field

with shadow like a thundercloud;

and o'er the gleaming king it bowed,

as huge aloft like mace he hurled

that hammer of the underworld,

Grond. Clanging to ground it tumbled

down like a thunder-bolt, and crumbled

the rocks beneath it; smoke up-started,

a pit yawned, and a fire darted.

(lines 3,558 to 3,573)

The Geste of Beren and Lúthien

J.R.R. Tolkien

See too http://oxfordinklings.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/the-flight-of-noldoli-from-valinor.html

See too http://oxfordinklings.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/the-flight-of-noldoli-from-valinor.html

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)